Nicole KolsterReporting for BBC News Mundo from Caracas

Nicole Kolster/BBC

Nicole Kolster/BBCWhen Edith Perales was younger, he enlisted in the National Bolivarian Militia, a civilian force created by the late President Hugo Chávez in 2009 to help defend Venezuela.

“We have to be a country capable of defending every last inch of our territory so no one comes to mess with us,” Chávez said at the time.

Sixteen years on, Perales, who is now 68, is joining thousands of other militia members getting ready for a potential US attack.

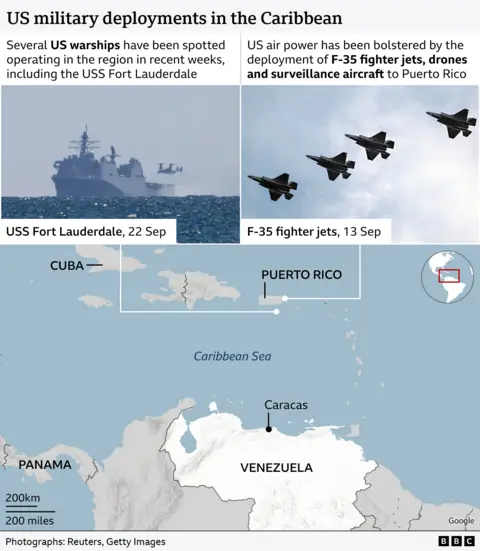

The rag-tag force, mainly made up of senior citizens, has been called up following the deployment of US navy ships in the South Caribbean on what US officials said were counter-narcotics operations.

Nicole Kolster/BBC

Nicole Kolster/BBCRead: What do we know about the US strike on ‘Venezuela drug boat’ and was it legal?

The US force has destroyed at least three boats it said were carrying drugs from Venezuela to the US, killing at least 17 people on board.

Venezuela’s defence minister, Vladimir Padrino, said the attacks and the US naval deployment amounted to a “non-declared war” by the US against Venezuela and President Nicolás Maduro swiftly called the militia into active duty.

Perales has got his uniform and boots at hand, ready to defend his “bastion” – the Caracas neighbourhood where he lives.

He lives in 23 de Enero, an area in the capital which has traditionally been a stronghold of Chavismo – the leftist ideology founded by the late President Chávez and adopted by his handpicked successor in office, Nicolás Maduro.

A loyal government supporter, he says he is “ready to serve whenever they call me”.

“We have to defend the fatherland,” he tells the BBC, echoing speeches given by President Maduro in the wake of the strikes on the boats.

Nicole Kolster/BBC

Nicole Kolster/BBCWhile experts have told the BBC that the deployment of US naval forces in the South Caribbean is large, they have also pointed out that it is not large enough to suggest that it is part of a planned invasion.

There is little doubt though that the relationship between Venezuela and the US – which has long been strained – has deteriorated further since Donald Trump returned to office.

The US is among a raft of nations which have not recognised the re-election of Maduro in July 2024, pointing to evidence gathered by the Venezuelan opposition with the help of independent observers showing that his rival, Edmundo González, won the election by a landslide.

Shortly after coming into office for the second time, Trump declared the Venezuelan criminal gang, Tren de Aragua, a terrorist group, which he has used as justification for deporting Venezuelan migrants from the US and for the recent military action in the Caribbean.

The Trump administration has also accused Maduro of being in league with drug cartels and recently doubled the reward it is offering for information leading to his capture to $50m (£37.3m).

Maduro has vehemently rejected Washington’s accusations and has defended his government’s actions against drug trafficking.

But the Maduro government has also co-operated with the Trump administration by taking back Venezuelan migrants deported from the US, whom US officials had accused of being gang members.

After the first boat strike, Maduro also sent a letter to his US counterpart calling for a meeting – an approach which has been rebuffed by the White House.

But his rhetoric internally has remained combative.

Maduro has ordered the Venezuelan military – the National Bolivarian Armed Forces (FANB) – to train local militias like the one to which Edith Perales belongs.

These groups are mostly made up of volunteers from poor communities, although public sector workers have reported being pressured into joining them as well.

In the past, the militia has mainly been used to boost numbers at political rallies and parades.

Its members tend to be much older than those who join the feared “colectivos” – gangs of hard-core government supporters which have been accused of committing human rights abuses and which are often used to break up anti-government protests.

But seemingly jittery in the face of what it perceives as a US threat, Maduro’s government is now training up the militia.

On a Saturday afternoon, soldiers fan out in Caracas’ Petare neighbourhood to fulfil Maduro’s order that “the barracks come to the people”.

The soldiers’ task is to teach the locals how to handle arms to respond to “the enemy”.

The training scenario includes tanks, Russian-made rifles – not loaded – and instruction posters.

A soldier is giving instructions to a small group on a loud speaker.

“The important thing is to familiarise yourselves with the weapons; we aim at the target and make a hit.”

Nicole Kolster/BBC

Nicole Kolster/BBCEveryone in the neighbourhood, including women and children, is listening.

Most of the volunteers taking part in the training exercise have no experience in armed fighting, but what they lack in experience they make up for in enthusiasm.

“If I have to lay down my life in battle, I’ll do it,” Francisco Ojeda, one of the locals taking part, tells BBC News Mundo.

The 69-year-old hurls himself on the sun-baked tarmac and holds a combat position as he clutches an AK-103 rifle. A soldier corrects his form.

“Even the cats will come out here to shoot, to defend our fatherland,” he says.

His eagerness is matched by that of Glady Rodriguez, a 67-year-old woman who recently joined the militia. “We are not going to allow any US government to come and invade,” she insists.

Home-maker Yarelis Jaimes, 38, is a little more hesitant. “This is the first time I grab such a weapon,” she says. “I feel a bit nervous, but I know that I can do it.”

But while the residents in Petare are learning to handle a rifle, outside of Maduro’s strongholds, life goes on as normal, with few seeming to give much thought to the possibility of an invasion.

Even just a few metres from where Francisco Ojeda was taking position in the dusty street, residents go about their daily routine unperturbed. Street sellers display their wares, while other people do the shop for the weekend without even glancing at the militia members carrying out their exercises.

Benigno Alarcón, a political analyst at the Andrés Bello Catholic University, says Maduro’s plan for the militia is not for it to engage in battle but rather to act as a “human shield”.

Prof Alarcón argues that by calling up civilians, the Maduro government wants to increase the human cost any potential US military action would incur by making the possibility of human casualties much higher.

According to Prof Alarcón, it therefore does not matter if the militia are not well trained or even if they are unarmed.

Maduro has claimed that more than 8.2 million civilians are enlisted in the militia and in the reserves, but this figure has been widely questioned.

Perales, who has been in the militia for decades, sees his role as a “defender” of his street, the neighbourhood where he lives, what he knows.

While he has taken part in previous training exercises, he has opted out of the more recent ones, due to his age and health.

But were a conflict to happen, he says he is ready: “We must defend the territory. To wear the uniform already implies a responsibility.”