Tony HanGlobal China Unit

Metropolitan Police

Metropolitan PoliceA woman, said by police to have bought cryptocurrency now worth billions of pounds using funds stolen from thousands of Chinese pensioners, has been sentenced to 11 years and eight months for money laundering.

After fleeing China, she moved to a mansion in Hampstead, north London. The Metropolitan Police raided it a year later and made one of the world’s single largest crypto seizures.

More than 100,000 Chinese people invested their money in her company – which claimed to be developing high-tech health products and mining cryptocurrency. In reality, she embezzled the funds, police say.

Investors have told the BBC World Service they hope to get at least some of their cash back from the UK authorities. Anything left unclaimed would normally default to the UK government – leading some to speculate that the Treasury could stand to gain from the haul.

“If we can gather all the evidence together, we hope the UK government, the Crown Prosecution Service and the High Court can show compassion,” said one victim we are calling Mr Yu, who says his marriage failed as a result of the fraud. “Because now, it’s only that haul of Bitcoin [cryptocurrency] that can return us a little bit of what we lost.”

Qian Zhimin, 47, arrived in the UK under a fake passport in September 2017, after Chinese police started investigating her.

She moved into a mansion on the edge of Hampstead Heath, at a rent of more than £17,000 ($22,700) a month. To pay for this, she needed to convert her Bitcoin stash back into money she could spend.

So she posed as a wealthy antiques and diamond heiress, and hired a former takeaway worker as her personal assistant, who she asked to trade the cryptocurrency into other assets, such as cash and property.

Metropolitan Police

Metropolitan PoliceAs Bitcoin rocketed in value, Qian could achieve what her company promised its investors – that they could “get rich while lying down”. Her assistant Wen Jian – at her own trial last year, which culminated in a six-year jail term for money laundering – said Qian had spent most of her days lying in bed, gaming and online shopping.

But Qian was also drawing up a bold six-year plan for future schemes, according to her diary. Her notes outline plans to found an international bank, buy a Swedish castle, and even to ingratiate herself with a British duke.

Her grander stated objective was to become queen of Liberland, an unrecognised microstate on the Croatian-Serbian border, by 2022.

In the meantime, Qian had Wen look for houses she could buy in London. But her attempts to purchase an especially large property in Totteridge Common – an area known for its substantial, secluded residences – triggered a police investigation when Wen was unable to account for her boss’s wealth.

Police raided Qian’s Hampstead rental property and uncovered hard drives and laptops found to be loaded with tens of thousands of Bitcoin – believed to be the single largest cryptocurrency seizure in UK history.

Qian had set up the company through which money was embezzled just four years earlier, in her native China. Lantian Gerui, or Bluesky Greet in English, claimed to use investors’ money to mine – or generate – new Bitcoin, and to invest in a range of pioneering technological devices.

But UK police believe this was an elaborate scam, and that Qian’s company was simply using promises of high profits to pull more and more investors into the scheme.

“The more information we got about her involvement… that she was actually the leader of the fraud, not just a lower down member… it became obvious that yes she’s very clever, she’s very switched on, very manipulative, able to persuade a lot of people,” Det Con Joe Ryan from the Met told the BBC.

One of her investors, Mr Yu, says he never suspected anything was wrong because the company drip-fed him a portion of his apparent earnings – just over 100 yuan ($14, £10) – every day.

“That made everyone feel really good, it even gave us the confidence to borrow a little more to invest in the company,” he says.

He and his wife had initially invested 60,000 yuan ($8,429, £6,295) each. They were told, he says, they would make a 200% profit over two and a half years. They were soon taking out thousands of pounds’ worth of loans at interest rates of up to 8%, in order to invest more.

In addition, Mr Yu reinvested his daily payouts back into the company as soon as he received them.

“There was no rule that you had to reinvest your earnings, but I suppose we were just too weak to resist. They just pumped up our dreams… until we lost all self-control, all critical judgment.”

Chinese social media

Chinese social mediaInvestors saw their daily payouts topped up for each new person they signed up. This helped the scam reach some 120,000 people, based in every one of China’s provinces, according to documents from trials in China of the company’s official promoters. Their deposits totalled more than 40bn yuan ($5.6bn, £4.2bn), the UK’s Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) has found.

A former company employee later testified that it was new investors’ money that had been funding the daily payouts, not crypto-mining dividends.

Lantian Gerui’s marketing exploited the loneliness of many middle-aged and elderly Chinese. Qian wrote poems about social responsibility, with lines such as: “We must love the elderly with the infatuation of a first romance.”

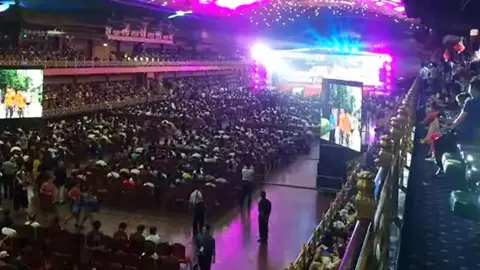

The company also organised mass holidays and banquets for current and potential investors. These were used to promote yet more investment opportunities – slideshows and card machines at the ready.

Lantian Gerui also trumpeted its love of China as a nation, another ploy calculated to appeal to the elderly.

“Our patriotism was our Achilles’ heel, that’s what they exploited,” says Mr Yu, who is in his 60s. “They said that they wanted to make China number one in the world.”

A range of speakers endorsed the company, including the son-in-law of the late Chairman Mao, the founding father of the People’s Republic of China – Mr Yu said.

“We in our generation all looked up to Chairman Mao, so if even his son-in-law was vouching for it, how could we not trust it?”

The company even held an event in the Great Hall of the People, where China’s legislature meets, according to an investor who attended the event and two others we spoke to.

“That bunch of [promoters], they’d take something red and persuade you it was white, take something black and convince you it was red,” Mr Yu says.

Despite leading this high-profile enterprise, Qian was notoriously secretive, known only as Huahua or Little Flower to her clients, and communicating with them largely through the poems she posted on her blog.

But she would emerge for the biggest investors – those who put in at least 6m yuan ($842,000, £628,000) – inviting them to more intimate events, according to one of these clients, Mr Li.

“Those of us present, you could say that we were starstruck,” he remembers. “We all saw her as our Goddess of Wealth.

“She started encouraging us to dream big… that within three years, she’d give us enough wealth to last our families three generations.”

Mr Li, his wife, and his brother, invested some 10m yuan ($1.3m, £1m) between them.

Alamy

AlamyA Chinese police investigation into Lantian Gerui, launched in mid-2017, signalled the beginning of the end for Qian’s scheme.

“The payouts suddenly stopped,” Mr Yu recalls. “The company said the police were doing some checks… though we were promised that payments would resume soon enough.”

What helped the investors initially keep calm, he says, was company managers’ reassurance that this was just a temporary blip, urging them not to approach the police.

What he later discovered through the Chinese court cases, he says, is that Qian had paid off those senior managers to assuage investors’ concerns – while she fled to the UK with the money.

Qian was not entirely oblivious to the plight of her investors – she outlined a plan in her diary to pay back her debts in China, once the price of Bitcoin had reached £50,000 per coin. But her diary makes clear that her priority was to rule and develop Liberland, earmarking millions of pounds for this project.

When she was finally arrested in York, in the north of England, last April, police also found four other people at the house, Southwark Crown Court heard at the start of her sentencing hearing on Monday. All four had been brought to the UK specifically to work for Qian in roles such as shopping, cleaning and security – and were employed illegally, the court was told.

At the time of her arrest, Qian denied all charges, claiming she was simply fleeing a Chinese government crackdown on crypto entrepreneurs, and disputing evidence presented by the Chinese police. But then, at her trial in September, she unexpectedly pleaded guilty to illegally acquiring and possessing the cryptocurrency.

Mr Li told the BBC this offered victims a “glimpse of sunlight”.

The cryptocurrency Qian brought to the UK has multiplied more than 20 times in value since her arrival. Its fate will be decided by a civil “proceeds of crime” case that will start in earnest early next year.

There are thousands of Chinese investors planning to make a claim in this case, say lawyers from two firms representing victims. But this will not be easy, one of them – a Chinese lawyer who asked to remain anonymous – told us. They will need to prove their claim – and in many cases they did not transfer money to Qian’s company directly, but to accounts of local promoters who then passed the cash up the chain.

It is not clear whether the victims, if successful, will receive only their original investment, or an inflated amount which reflects Bitcoin’s subsequent rise in value.

As in other “proceeds of crime” cases, any money left over after this process would normally default to the UK government. The BBC asked the UK Treasury what it plans to do with any remaining money, but it did not respond.

Separately, last month, the CPS said it was considering a compensation scheme for those with no representation in the civil case. We asked the CPS what level of evidence this alternative scheme would require, but it told us it was not able to share any details at this stage.

The toll on Mr Yu – whose wife invested alongside him – has not just been financial, but personal, culminating in divorce and little contact with his son, he told the BBC.

Still, he considers himself relatively lucky. One lawyer we spoke to said many of Qian’s investors were left without money for food or medicine.

Mr Yu knew one such person – from Tianjin, northern China. She died of breast cancer after discharging herself from hospital, unable to afford treatment, he said.

“She was at death’s door, and she knew I could write, so she asked me to write her an elegy if the worst came to the worst.”

Mr Yu says he kept his word and wrote a poem in her memory which he posted online. It ends with the lines:

“Let us be pillars, holding up the sky / Rather than sheep, to be led and misled / To those who survive – strive harder / That we might right this grave injustice.”