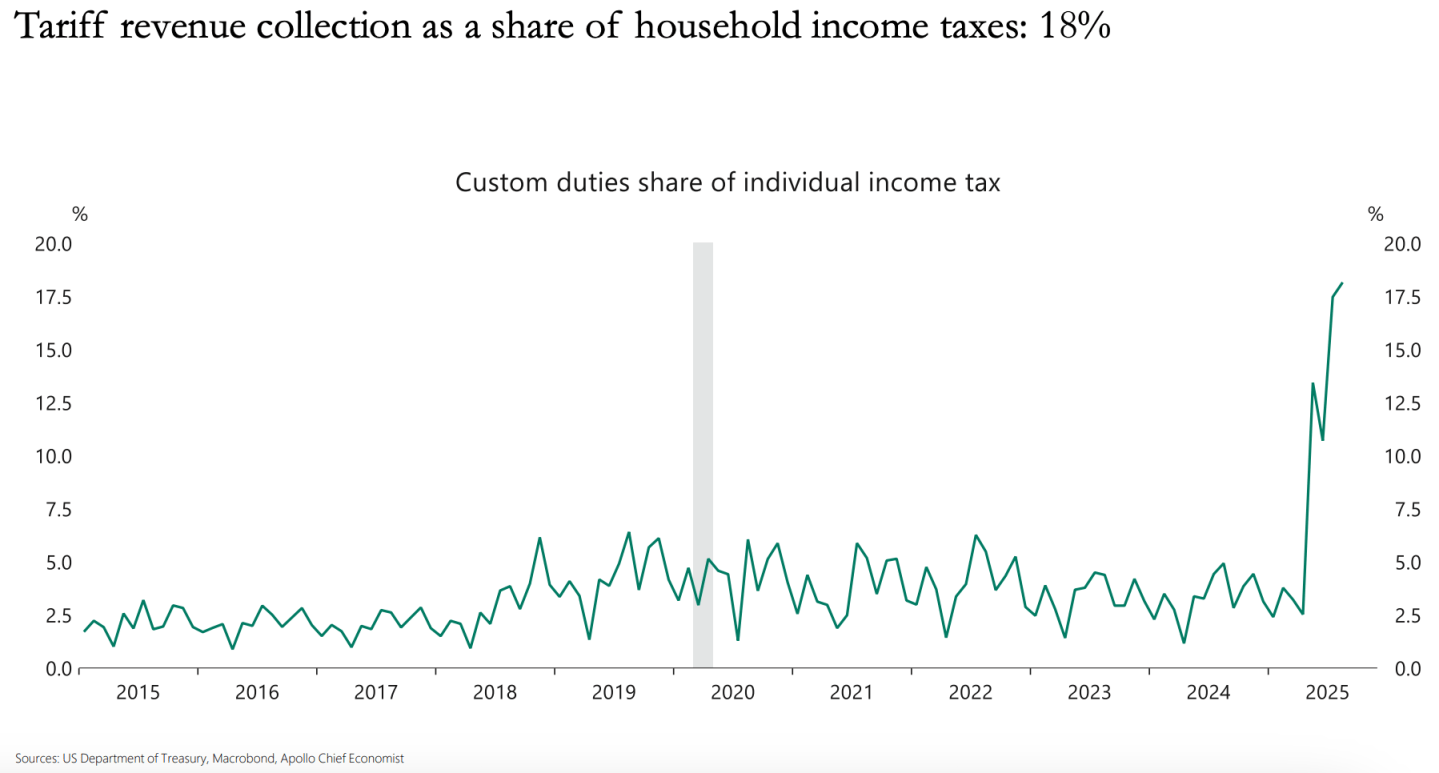

The U.S. government is currently collecting tariff revenues at an annualized pace of roughly $350 billion, a “significant” amount, according to Torsten Slok, chief economist at Apollo Global Management. In his typical style, one of brevity and striking charts, Slok added that the figure equates to roughly 18% of annual household income tax payments, underscoring that tariffs are not a marginal tool but a significant revenue source shaping America’s economic and trade landscape.

Tariffs—essentially taxes imposed on imported goods—have long been a controversial instrument in U.S. economic policy. Traditionally used to protect domestic industries or raise public funds, they have re-emerged in recent years as a centerpiece of trade strategy. The scale of collection today, at $350 billion annually, marks one of the most substantial contributions in recent history.

Fortune Senior Editor-at-Large Shawn Tully and Steve Hanke, the economist famously known as the “money doctor” for his expertise on hyperinflation, have argued that the tariffs are no more than a value added tax, something well known in Europe since shortly after the end of the Second World War. Tully and Hanke argue that the tariffs constitute “America’s answer to Europe’s fatal attraction that’s long been the leading enabler for the region’s extremely high levels of government spending.”

“The bottom line is that the amount of money collected in tariff revenue is very significant,” Slok argues. Given President Trump’s reluctance to raise taxes elsewhere, that may be the point.

Tariffs and household impact

While tariffs bring in significant funds, the burden is not evenly borne. Economists widely agree that tariff costs are passed along to consumers. When the government imposes a tax on imported goods, retailers and wholesalers often raise prices, which can lead to higher consumer costs across a range of products from electronics to household goods.

For households, this effectively means that tariffs act as an indirect tax. Unlike income tax, which is based on earnings and progressively structured, tariffs apply equally to everyone purchasing affected goods. This can make them more regressive, as lower-income families spend a higher share of their incomes on consumer staples. The $350 billion figure therefore not only signals higher fiscal collections but also a widespread, though less visible, tax on consumption. It’s a lot like a shadow VAT, to Tully and Hanke’s point.

Impact on the National Debt

The nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), while not commenting on whether the tariffs constitute a tax, has also recognized their significance as a source of federal revenue. The CRFB argued in August that the surge in tariff collections presents a significant, though not all-encompassing, step toward managing America’s $37 trillion national debt.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has agreed, projecting that they could reduce the deficit by up to $4 trillion over the next decade. The CBO estimates the primary deficit would shrink by $3.3 trillion over 10 years, with an additional $700 billion in savings due to lower interest payments on the national debt—bringing total deficit reduction to $4 trillion. This revision is notably more optimistic than a CBO report from June, which tallied a $2.5 trillion deficit decrease plus $500 billion in interest savings due to more limited tariffs implemented earlier in the year.

However, even these hefty figures must be understood within context: U.S. government expenditures still far outstrip this revenue, with income and payroll taxes covering more than three-quarters of all federal receipts. That scenario would resemble a European-style escalation of spending, with books being balanced in dysfunctional fashion by a tax on consumers.

Experts caution against overestimating tariffs’ deficit-busting powers. While meaningful, the funds are only a fraction of what’s required to close the debt gap outright. The CRFB, for example, notes that recent tariff gains, if permanent, would “meaningfully reduce deficits,” but cannot halt national debt growth alone—especially given commitments to entitlement programs and rising interest costs.

Who pays—and who benefits?

While the government sees increased revenue, the real cost of tariffs is largely paid by American consumers and businesses. Retailers typically pass tariffs along as higher prices, making them function as a regressive tax that disproportionately impacts lower- and middle-income families. According to Yale Budget Lab, families in the second-lowest income tier now pay on average $1,700 more annually, while those in the highest tier shell out upwards of $8,100 due to tariff-related cost increases.

Not all effects are domestic. Defense and infrastructure advocates assert that tariffs also drive up the price of critical supplies, complicating procurement for national security and public projects.

President Trump has floated distributing “tariff dividend checks” as a direct rebate to families, but most economists say that—given government spending’s sheer scale—even record-breaking tariff inflows would mainly slow debt growth, not reverse it. Political and economic experts continue to debate whether the benefits from tariffs in the form of revenue and trade leverage are outweighed by the higher prices felt by American households and their broader economic impact.

In sum, U.S. tariffs have rapidly evolved from a modest funding tool to one of the most significant—and contested—sources of federal revenue. With projections now in the trillions, they may help slow debt accumulation, but remain only a piece of a much larger fiscal puzzle.

For this story, Fortune used generative AI to help with an initial draft. An editor verified the accuracy of the information before publishing.