Pain is hard to measure. One person’s “ouch” is another’s agony. Now, scientists say they’ve found a better way of assessing pain: putting a price on it. By translating pain into dollars, they’ve created a more accurate, comparable way to measure suffering.

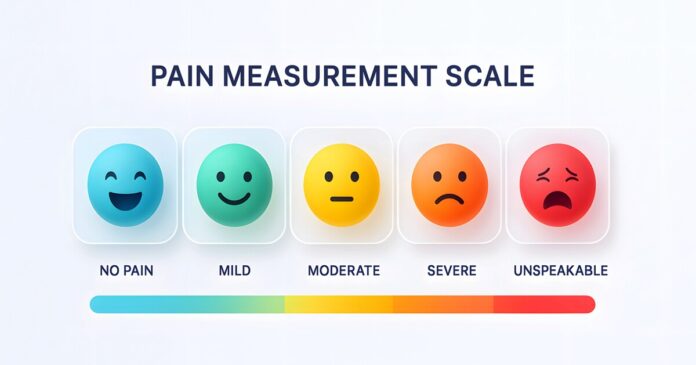

If you’ve been an inpatient in a hospital with a painful condition or following surgery, you have very probably been asked, “How would you rate your pain on a scale from zero to 10?” While it’s widely used, the limitations of this approach are well-known and boil down to this: one person’s “10” is another person’s “4”.

In a study led by the UK’s Lancaster University, researchers investigated a novel way of accurately – and more objectively – assessing people’s pain, and it came down to translating pain into something that’s familiar to everyone: money.

“We’ve all been asked to rate our pain from one to 10 – but one person’s three might be another’s five, and those numbers can shift with experience,” said Carlos Alós-Ferrer, Chair Professor of Economics at Lancaster University Management School and the study’s corresponding author. “Our research proposes a better way: turning pain into money – not to commodify suffering, but to create a scale we can all share.”

Inaccurate pain measurements can lead to inadequate pain management. For people with chronic conditions, this can mean a reduction in quality of life. In addition, the global cost of treating pain is enormous (and complex). In the US alone, the estimated cost was between US$560 billion and $635 billion per year. That figure, which is now 15 years old, comprises direct healthcare costs, days off work, hours off work, and lower wages. It’s understandable, then, that the researchers would want to investigate a better system of pain measurement.

They ran three randomized experiments with 330 healthy adults aged between 18 and 60. In one, participants were exposed to mild electrical pain; in another, it was heat pain; in the third, participants received the same heat stimulus but were given either a placebo or a topical anesthetic. In each experiment, participants completed three standard pain scales for comparison: the numerical (0-10) rating scale; the visual analog scale, and the general labeled magnitude scale (gLMS). The gLMS is a tool where pain intensity is rated along a line with verbal anchors such as “no sensation” to “strongest imaginable sensation”.

Alongside these pain assessments using traditional methods, the researchers tested their “monetary equivalence” (ME) method. Participants were repeatedly asked whether they would accept a certain amount of money to experience the same painful stimulus again, or choose a smaller amount to avoid it. Example: “Would you rather get 15 Swiss francs and feel the pain again, or 10 Swiss francs and no pain?” The point where a participant switched from “no pain” to “pain” revealed how much the pain was “worth” to them in monetary terms. Two versions of the ME method were tested: ME1, where questions were listed in increasing order of money (enforcing consistency); and ME2, where the same questions were asked randomly (allowing for some inconsistency).

Across all three experiments, the monetary methods (ME1 and ME2) outperformed the traditional scales at distinguishing between high- and low-pain conditions. Effect sizes – that is, how strongly the measure distinguished between groups – were dramatically larger for ME1 and ME2 (“very large”) compared to standard pain scales (“small to medium”). Even in the analgesic study, where traditional scales often failed or even showed misleading results (for example, participants reporting more pain after receiving an analgesic), the monetary measures correctly and significantly detected differences. This likely happened because participants expected the anesthetic to eliminate the pain completely, and when it didn’t, they rated their pain higher. It’s a psychological effect the monetary method avoids.

Statistical analyses showed “decisive evidence” that the monetary methods predicted pain levels much better than standard ones. Further testing confirmed that ME1 was the most accurate predictor of whether someone had been in the high-pain group, even when controlling for factors like income or gender. Moreover, the ME approach worked for both electrical and heat pain, suggesting it’s not limited to a specific kind of stimulus. It remained reliable even when participants didn’t know whether they’d received a placebo or analgesic, showing the method is resistant to psychological “expectation effects.”

“Different people still will put a different price on the same pain, but there is no problem interpreting the question,” Alós-Ferrer said about the new method. “As a result, measurements are more precise and the shift from low to high levels of pain is clearly reflected in the monetary scale. This makes it useful for clinical trials to study the effectiveness of painkillers and treatments, because the participants are randomly assigned to different groups.”

As with most studies, this one had limitations. Participants were mostly Swiss uni students, so results may not generalize to older, more diverse, or clinical populations. Because money means different things to people with different incomes, richer individuals might report higher “pain prices.” Random group assignment controls for this in experiments, but real-world use would require adjustments. The study used short, controlled pain stimuli. Chronic pain is a different beast; more complex, it involves emotional and functional dimensions not captured in the present study. The researchers note that more diverse trials, including chronic pain patients, are needed before the method can be used clinically.

Despite its limitations, the study points to several promising uses for a monetary pain scale. In clinical trials, it could dramatically improve the sensitivity of pain measurements when testing new painkillers or other treatments. In the research setting, it provides a more objective way of comparing pain experiences across participants, making results more reliable and reproducible. And in the clinical setting, a monetary pain scale could be used to help tailor pain management plans by quantifying the “cost” of pain in ways that standard scales can’t.

The study was published in the journal Social Science & Medicine.

Source: Lancaster University